Summer 1985, DH at Tanglewood with Leon Kirchner and Adrienne and Louis Krasner following the premiere (coached by Louis and dedicated by me to him) of my revised String Quartet No. 1 by a fellowship quartet. It was a great honor to work with Kirchner & Louis that summer, and to eagerly take in all the oral history Louis had to offer about Berg, Schoenberg, and Webern.

Louis Krasner was the shortest person in the room, but he undoubtedly cast by far the longest shadow. The summer’s fellowship composers (of which I was one during summer 1985) arrayed themselves easily, thoughtlessly, like bolts of cloth, with the bodily flexibility available only to the young, over, and around sticks of furniture in the living room at Seranak—onetime home of Serge and Natalia Koussevitzky, and by that time, serving as a venue for the Tanglewood Festival. We were gathered for an oral history lesson (one he’d clearly presented before and would present again) from the person who had premiered not only Alban Berg’s, but also Arnold Schoenberg’s monumental violin concertos—a man not only present but literally instrumental in bringing about their existence.

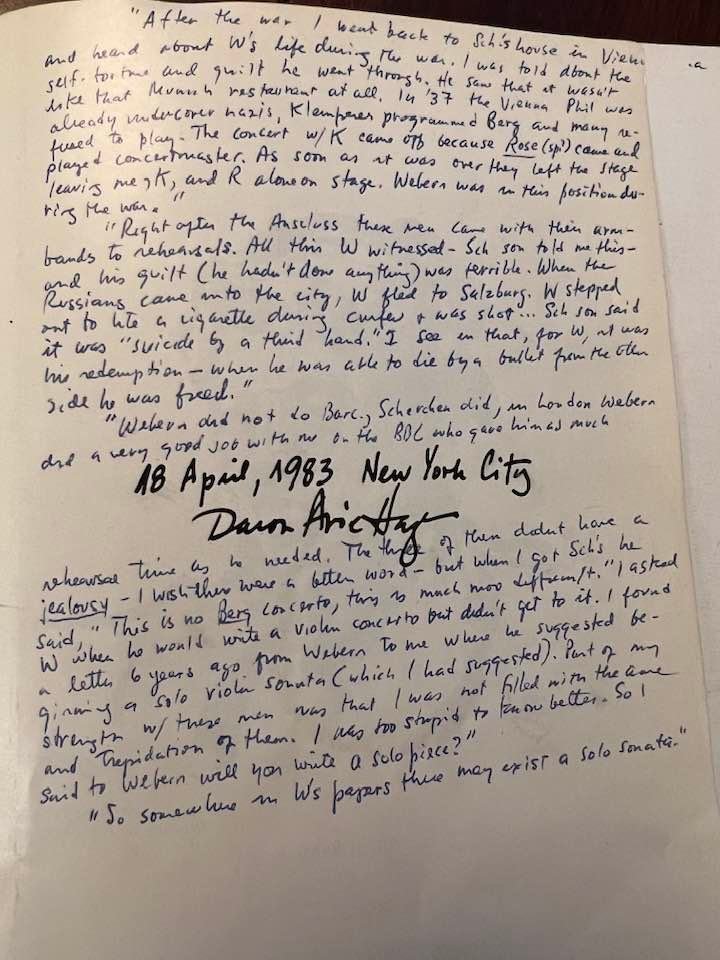

Observing as a child that my parents customarily inscribed the date and place that they had acquired books on the title page, I had long followed suit; so, I knew that the Universal study score of the Berg concerto I was holding had been purchased at Patelson’s (lamented emporium behind Carnegie Hall) on 18 April 1983, after a lesson with Lukas Foss, whose astonishment that I did not yet know the piece (there certainly was a lot that I didn’t know then that I know now—and I have learned the obvious fact that the more you know the less you know) transformed in a beat to wild enthusiasm and joy as he sat down without a score in front of him and played for me at the piano the climactic moment—the hochpunkt at measure 125 of the second movement—singing in his own octave the solo violin part.

Nobody had a cell phone back then, and I don’t think that it would have occurred to any one of us to bring a tape recorder. We were surrounded by history: Leon Kirchner was our teacher; Maurice Abravanel perambulated and dispensed wisdom every afternoon; John Adams listened to our music one afternoon before attending a rehearsal of his brand new Harmonielehre; Bernstein was due in a week or two and would listen to our music and spend the evening in this same room, cross-legged on the floor, talking about Art and the Bomb. Knowing that I was a witness to something important I pulled a ballpoint pen out and began to transcribe Louis’ words; the only paper at hand was my study score, so I wrote on that.

“The Schoenberg concerto is certainly the equal of the Berg,” he began. “Though not as popular, even if it takes a hundred years, it will become the pride of violinists. The Berg, sentimental, with a requiem story, had everything going for it. The Schoenberg, when Stokowski finally programmed it, was rejected twice before being accepted. There was no fee involved; Stoki paid me out of his own pocket.”

“Stoki,” he continued, “was the ‘Glamorous One,’ but he forced the check on me and made the subsequent performances possible of the Berg and Schoenberg concertos in the States. People should know that. Stoki was really the first performance of the Berg in the States—before Koussy. Mitropoulos was one of the greatest proponents of contemporary music. He would sleep for only four hours a night. He got his reward—by dying on the podium at La Scala.”

I looked around. It was plain that we all knew that we were hearing something special. Louis had known Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg. He had been there. “These three men were complicated, but the period in which they lived was the fermentation of world calamity—in a way, we are still in that time. Webern was gentle, humble, frail (like Bartok)—very intense. About Webern all you could see were suspicious, blazing eyes. Devoted to his family—religious, with a family stretching back to the 1500s. I went with Webern from Vienna to Barcelona at a time when Berg died—December of 1936—I was in New York and involved with a new string quartet. I withdrew in order to play the Berg for the ISCM in Barcelona. I dropped everything and went to Vienna. Webern came and was to conduct it but withdrew. No one knew it but him. I said ‘let me go’ to Webern and they said, ‘No! He’s in too emotional a state’.”

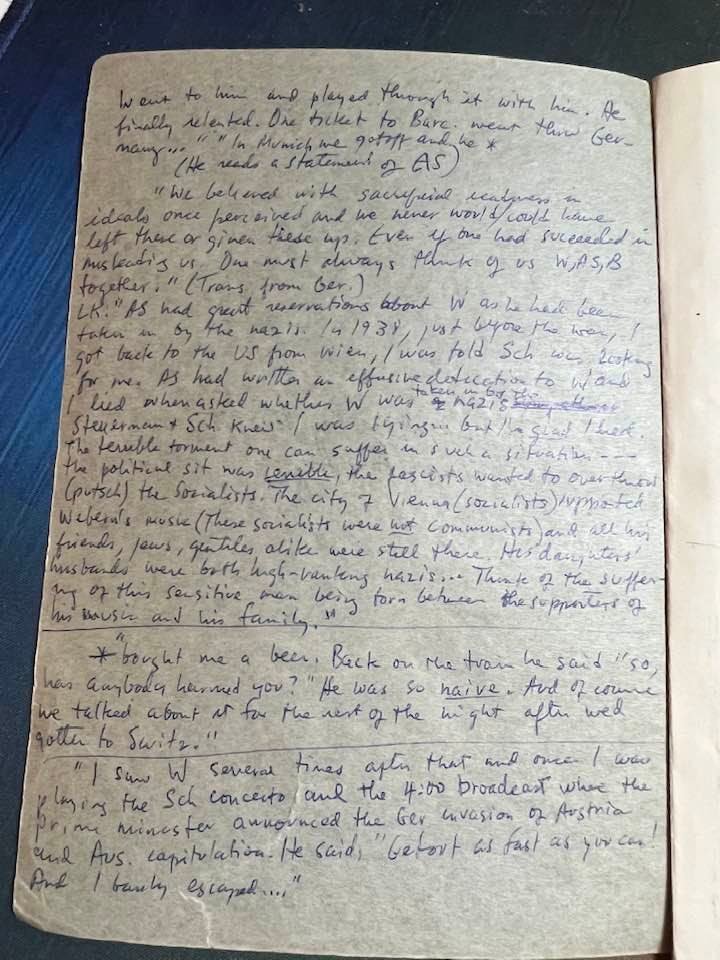

“Finally, I went to him and played through it with him. He finally relented. One ticket to Barcelona went through Germany. In Munich we got off the train and he bought me a beer. Back on the train he said, ‘so has anybody harmed you?’ He was so naive. And of course, we talked about it for the rest of the night after we’d gotten to Switzerland.”

At this point, he read a statement of Arnold Schoenberg, which he had translated himself: “We believed with sacrificial readiness in ideals once perceived and we never would/could have left these. Or given them up. Even if one had succeeded in misleading us. One must always think of us as Webern, Schoenberg, and Berg together.”

Putting the paper down, Krasner continued in his own words, “Schoenberg had great reservations about Webern as he had been taken in by the Nazis. In 1938, just before the war, I got back to the US from Vienna; I was told that Schoenberg was looking for me. Schoenberg had written an effusive dedication to Webern and I lied when asked whether Webern had been taken in by the Nazis. Steuerman and Schoenberg knew I was lying, but I am glad that I lied…. The terrible torment one can suffer in such a situation—the political situation was terrible, the Fascists wanted to overthrow (putsch) the Socialists. The city of Vienna (Socialists) supported Webern-s music. These Socialists were not Communists. And all his friends—Jews, Gentiles alike—were still there. His daughters’ husbands were both high-ranking Nazis…. Think of the suffering of this sensitive man being torn between the supporters of his music and his family.”

“I saw Webern several times after that and once I was playing the Schoenberg concerto and the 4 o’clock broadcast where the prime minister announced the German invasion of Austria and Austria’s capitulation. He said, ‘Get out as fast as you can!’ and I barely escaped.”

“After the war, I went back to Schoenberg’s house in Vienna and heard about Webern’s life during the war. I was told about the self-torture and guilt he went through. He saw that it wasn’t like that Munich restaurant at all. In ’37, the Vienna Philharmonic was already [filled with] undercover Nazis. Klemperer programmed Berg and many refused to play. The concert with Klemperer came off because Rosé came and played concertmaster. As soon as it was over they left the stage, leaving me, Klemperer, and Rosé alone on stage. Webern was in this position during the war.”

“Right after the Anschluss these men came with their armbands to rehearsals. All this Webern witnessed. Schoenberg’s son told me this—and his guilt (he hadn’t done anything) was terrible. When the Russians came into the city, Webern fled to Salzburg. Webern stepped out to light a cigarette during curfew and was shot…. Schoenberg’s son said that it was ‘suicide by a third hand.’ I see in that, for Webern, it was his redemption—when he was able to die by a bullet from the other side, he was freed.”

“Webern did not go to Barcelona, Scherchen did. In London Webern did a very good job with me on the BBC who gave him as much rehearsal time as he needed. The three of them didn’t have a jealousy—I wish there were a better word—but when I got Schoenberg’s concerto he said, ‘This is no Berg concerto; this is much more difficult!’ I asked Webern when he would write a violin concerto but he didn’t get to it. I found a letter six years ago from Webern to me where he suggested beginning a solo violin sonata (which I had suggested). Part of my strength with these men was that I was not filled with awe and trepidation of them. I was too stupid to know better. So I said to Webern will you write me a solo piece?”

“So, somewhere in Webern’s papers there may exist a solo sonata.”