The Loomis Chaffee Academy

Mark Gottschalk

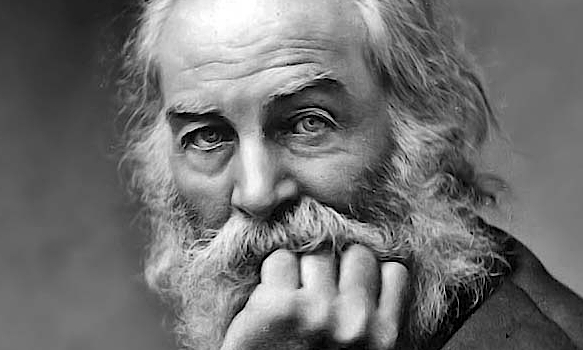

Composers create new works the way that Johnny Appleseed threw seeds around. We’re gardeners. Some of the things we plant die, some flourish, and some sit, oddly dormant, for many years, before springing into life. Such is the case with my Walt Whitman Requiem, which E.C. Schirmer is publishing in September, and whose release I celebrate with greater excitement than I have any new work for years.

The fact that my Walt Whitman Requiem required the longest developmental period of any work in my compositional œuvre—fully thirty-three years from first sketch to final draft—is an indication of the seriousness with which I approached the project. The work was first commissioned by Mark Jon Gottschalk for performance by the Loomis Chaffee School chorus and string orchestra, with Susan Valcq Gottschalk soprano soloist. Although I had composed several works previously premiered by major ensemble—including Prayer for Peace, which the Philadelphia Orchestra had premiered shortly before this work was begun—the requiem is, in fact, the first commission I received as a professional musician. Gottschalk was a close friend of my brother Kevin’s, and this gesture of faith in my abilities came, in my mind at least, from them both. I began it in New York City and completed it at Yaddo, the artist retreat in Saratoga Spring, New York, during my very first artist residency there, in August 1984.

“I bought myself breakfast at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel on Central Park South to celebrate,” I recalled in a 1998 Wisconsin Public Radio interview. “Even though I didn’t have the rent money, it seemed the thing to do to mark what I hoped would be a career blessed with lots of meaningful (and profitable) commissions.” In fact, the work came to represent to me a deeper understanding of what being a composer entailed, since I immediately began to feel that it required revision. Nevertheless, Gottschalk premiered the first version of the Mass on 10 May 1993 at the Loomis Chaffee Academy, a prestigious boarding school in Windsor, Connecticut. I don’t recall ever having received a recording of the performance. Life, other projects, and, to be honest, a sort of discomfort at not having gotten right my very first big commission, prompted me to set the thing aside.

Michael Haithcock

In 1999, former president of the College Band Directors National Association and the leading spirit behind the commissioning of my opera Bandanna, the premiere production of which he conducted, Michael Haithcock, had taken on the leadership of the bands at the University of Michigan. He was on the prowl for large works for chorus and band, and asked after the requiem. A small consortium of colleges was assembled to underwrite my revisions to the work and the re-orchestration for large wind ensemble. At that time, I added a movement—the Trope, in order to more acutely focus the work on Whitman’s identification with the young Civil War soldiers he equated with Jesus in the poem that I had chosen to intercut with the final Libera Me. As fate would have it, I executed most of the work at Yaddo, during another halcyon summer there. I extracted the parts, sent them off, and then … nothing. It was as though the piece was cursed. I immediately turned my attention to other projects, and it slipped out of my thoughts again. Robert Schuneman, whose early and staunch support of me as a publisher—not to mention wise tolerance of my crazy foibles as a brash young composer—had taken on the first version of the requiem back in 1984, and had high hopes for it, although he considered it “far too difficult as it stands for the mainstream choral market.” It had sat, available, but in manuscript, unperformed, but not entirely forgotten, in ECS’ Boston warehouse, across the street from Fenway Park.

Robert Schuneman

In summer 2017, both Bob and his wife Cynthia having passed away and the company acquired by Canticle Distributing in the Midwest, the requiem had come to me to represent a lost child when an Email from Stanley Hoffman, E.C. Schirmer and Galaxy Music’s Chief Editor asking what I was going to do with it made me pull the score from the shelf to take a hard look at it. Placing it on the piano rack and playing through it, a hundred memories flowed through my fingertips as I confronted the young composer hubristically spending money that he did not have on breakfast at Deverieux’s to celebrate a piece that was in fact in no way complete. I thought of the Britten War Requiem, to which it bore an obvious and, possibly, crippling debt, as I played. Reaching the final double bar, I realized that I had to now decide whether to withdraw the piece, accept defeat, and move on, or go back in one last time, thirty-three years older, and not try to “fix it,” but try to chip away whatever stone was left around the ideas to reveal what that nervy young composer had had in mind.

The 1999 and 2017 versions, side-by-side.

After several weeks, I completed another pass through the work during which I eliminated some of the more self-indulgent range requests of the singers, all of the quirky harmonic spellings that my immature ear had led me to use when notating the (very) chromatic, demanding music. After the practical experience of having composed nine operas, I was able to make the piece only “as hard as it needed to be” and no harder. I've grown up a lot. Honoring Gottschalk, my brother, Schuneman, Haithcock, and Hoffman—all of whom kept faith with the work (and, by extension, me) even when I did not—I put down double bars at the end of the thing for the third time in 33 years and now consider it finished. I’m proud to have one of the very first pieces that my first publisher ever took on finally issued in a form that I think appropriately manifests its subject.

How did I celebrate? By pouring myself a cup of coffee, carrying it out into the back yard of our home in Upstate New York, a wiser, more humble and reverent man, setting it down, and, noticing that the rhubarb needed watering, turning my attention to gardening.