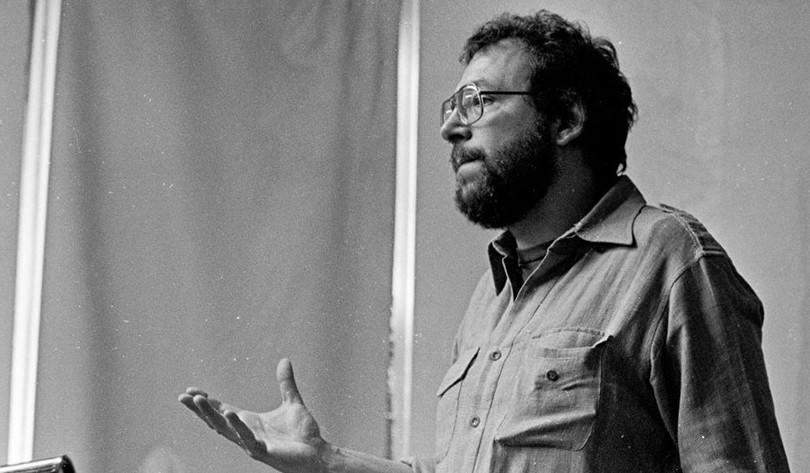

For my particular friend Mel Rosenthal, photography was an instrument for social justice. His Leica thrust before him like Quijote’s spear, he hurled himself into the back of squad cars in the South Bronx to raise awareness of social issues surrounding poverty and equality, into the Tanzanian countryside during the 70s to document medical care, into the Nicaraguan countryside to witness the effects of the revolution there. Mel was incredibly well-read, and taught English at Vassar for a few years. (We were both devoted readers of the Aubrey-Maturin books, which Mel could quote at length.) “Antonioni’s Blow Up blew my mind,” he told me once over Mescal one winter during the 80s at the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. “I didn’t have a damned clue, but I knew I needed to be a photojournalist.” In time, Lisette Model mentored him. He was Susan Sontag’s age, and had a huge crush on her; he used to tease me about the fact that I, 22 years his junior, had one, too.

He joined the faculty at Empire State College in 1975, and added artist mentor to his folio. But he never considered himself an academic. “I’m a messenger,” he told me once. “You touch people with notes; I do it with images. I take their pictures and give them back their image; you listen to what they say and give it back to them in music.” He was a poet addled by one-hundred-too-many waltzes with malaria, kicks in the ribs in pursuit of a shot, and the broken heart of a man who couldn’t—wouldn’t—forget the things he’d seen. Another winter in Virginia, we wept together, tenderly passing pages of our mutual friend Jerome Badanes’ just finished manuscript of The Final Opus of Leon Solomon to one another as Jerry sat, head in his hands by the fire, vulnerable and over-exposed.

Mel was a clear-eyed sentimentalist who could handle himself. When Gilda Lyons and I married, Mel—to our astonishment and trepidation—volunteered to photograph our wedding. In the event, Mel covered our wedding like an infiltration of enemy territory. Shoulder to shoulder with my bride before our priest in Rhinebeck’s Church of the Messiah, ring poised over her extended finger, I looked into our priest Gerald Gallagher’s eyes and followed his gaze downwards to see Mel, flat on his back at our feet, framing up a Gregg Toland-style hero shot. Gallagher, a tolerant, intelligent man, whispered, “Mel, I’m not sure that this is appropriate.” Swinging the camera away from his face with an enormous grin, Mel wasn’t about to take orders from a priest. “I don’t work for God … or for you, Jerry” he said, and got back to it. “The guys with the Berettas on Bathgate trusted me,” he told my father-in-law Bernie at the wedding reception, “because they knew I was a stand-up guy.” “But you still know why there’s a bat leaning against the wall by my front door,” Bernie, a classics scholar from South Buffalo, observed, in return. “Of course,” Mel laughed.

When the opera I’d written with Paul Muldoon called Vera of Las Vegas debuted at Symphony Space in 2003, Mel decided that he wanted to document it. Gilda stepped in at the last moment to portray one of the Catchalls. Opening night, Mel and I sat beside Leonard Garment, Ned Rorem, and Gary and Naomi Graffman at a catwalk-side cocktail table in the Leonard Nimoy Thalia. During the “Strippers’ Chorus,” Mel’s unerring sense of where the true story lay compelled him to document the following scene not in the opera but arguably more interesting: Gilda was staged with her derriere poised above our heads. Mel’s camera snapped as Naomi observed, gimlet-eyed, to me, “And you’re expecting her to count seven against five, for godsake.” Len, peering up at one of the Catchalls, touched my arm and said, “you’re a twisted man, Daron.” Mel photographed Gary as he gazed at Shequida like a cobra hypnotized by a mongoose. “This,” I replied to Len, “coming from Richard Nixon’s lawyer.” Sound of shutter clicking. “Yes, well—,” Len replied. Mel’s camera clicking again, capturing Len’s pride in his son (my Curtis classmate) Paul, playing a solo in the little cabaret ensemble as he absent-mindedly remarked, “The President didn’t wear fishnet stockings.” Beat. “That I know of.” Beat. Shutter-click. Mel, in heaven, shooting every face, mapping each reveal. Ned, genuinely curious: “How can Gilda sing in that getup?”

Visual artist and professor Bobbe Perry probably saved us all from scurvy one summer at VCCA, building beautiful soups from whence we all spooned wholesome lunches during a rocky period in the kitchen. She and Mel fell in love that summer and made one of the most beautiful couples I’ve ever known. They were like Dickinson’s “two butterflies,” in their questing hearts and profound mutual understanding. Both deeply-committed, sensitive artists who really knew one another. They lived around the corner from us on West End Avenue for years. Five years ago, we moved to the country. “Not enough pavement for me there,” groused Mel when Bobbe tried to get him to their country place. “It makes me tense.” We no longer ran into one another at artist colonies, or late at night, or when the dog needed walking, or over produce at Gourmet Garage, or at friends’ openings, and funerals.

In 2001, at our annual Halloween party, I was Diego Rivera, Gilda was Frida Kahlo, Bobbe was radiance itself, and Mel came as Che Guevara. The tiny apartment was packed with mutual friends and even some people that nobody knew, adult beverages were consumed, everyone was sweaty, Jerry Badanes and absent friends were toasted, righteousness was summoned, at one point the Internationale was sung. He pulled In the South Bronx of America off the shelf and read the inscription he’d written in it the previous March: “For my old loyal shipmate and particular friend Daron. May we continue to have wonderful voyages together. Love, Mel.” I hugged him fiercely. “I was lost on the infinite sea,” I sang into his ear, “but I’ve seen where she’s bound for.” He closed his eyes. He knew the Melville. And he knew the Britten. “There’s a land where she’ll anchor forever.”

We’re gonna be okay, Mel; forever’s a long time, but we know where you’re bound for.

This piece has been syndicated in the Huffington Post. To read it there, click here.