The bit was in. I had spotted bliss—far off in the distance still, but real enough to enthrall. Fifteen years old, summer of 1976, body vibrating, ablaze with youth and hormones at the kitchen table at three in the morning with the radio on listening to Ron Cuzner’s overnight jazz show on WFMR and copying parts to Together, the musical I was writing for my friends.

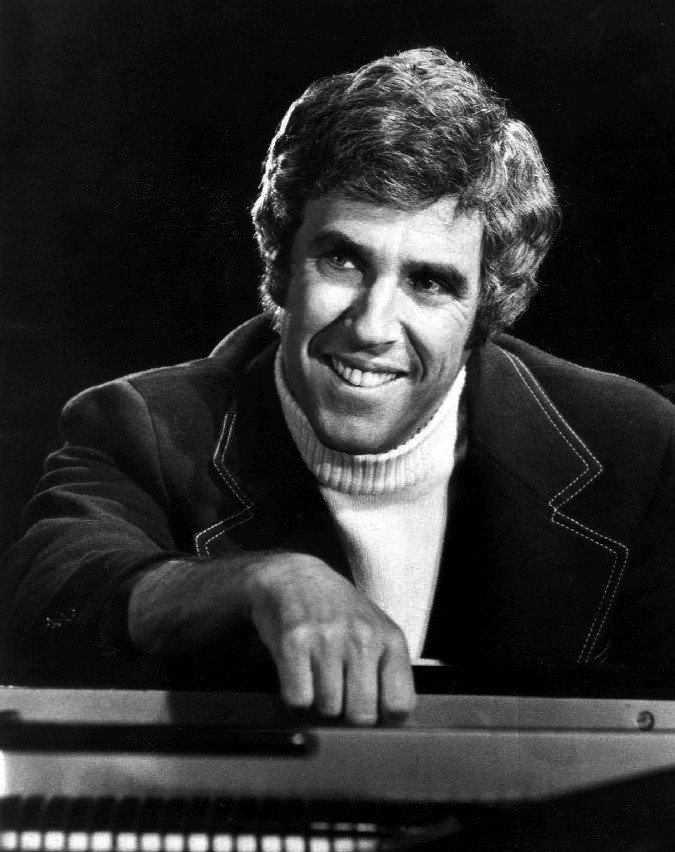

Cuzner introduced the six-minute-long 1971 Polydor recording to his listeners as though disclosing classified information over whisky to a fellow agent in a smoky bar near Checkpoint Charlie. I remember the words clearly: “He hails from California. (beat of silence) Marlene Dietrich (again, the silence, to let the enormously important intelligence land) is reported to have (beat) loved him. He married a glamorous movie star (beat), Angie Dickinson. But he was a student of Milhaud, and Cowell (I knew who these guys were and was impressed) who, shall we say, went off the railswith the likes of (he paused, as though about to invoke a Holy Trinity) Warwick, Jones, and Alpert. This (Cuzner’s ultimate seal of approval) very cool orchestral work describes the moment you first see (long beat) her.”

Five years earlier, my brother Kevin had brought the Columbia LP’s of Leonard Bernstein’s MASS home and I had scandalized my fellow ten-year-olds by playing “it was goddamn good” (listen to Alan Titus sing it here) in class at Linfield School to the horror of Principal Buege (pronounced “Biggy,” of course) and to the delight of my mother. (Kevin had provoked similar outrage by bringing Jesus Christ Superstar to school a year earlier.) But my mom also adored Ella Fitzgerald, Barbara Streisand, and Frank Sinatra—the exquisite Nelson Riddle arrangements of the Cole Porter songbook especially. I was immersed in the Beatles songbook, of course; I had read Twilight of the Gods, Wilfred Mellers’ terrific book about their songs, the previous summer. My brothers and I had wept in 1970 when the announcer introduced the first local broadcast of The Long and Winding Road on WOKY by revealing that the Beatles had decided to split up.

Intuiting that something interesting was about to happen, I slipped a cassette in to tape it, missing the first few bars. I would listen to that recording of And the People Were With Her a hundred times that summer. I still have it.

My literature teacher, Diane Doerfler, knew that the one thing I was sure I was going to do was leave Wisconsin for the coast at the very first opportunity. Which coast was very much up in the air. My father favored the west coast: he recorded movie soundtracks by way of a jack he had installed on the back of our television. I’d spent a lot of time listening to dozens of them—particularly to Elmer Bernstein’s majestic Great Escape, Magnificent Seven, and To Kill a Mockingbird. Doerfler was in favor of the east coast: she had tossed me a copy (which I still have) of John Cheever’s collected short stories about life in the Hudson Valley and quipped, “Here. Read these. They will help.” (They did. Doerf was right; after decades in Manhattan, I now live in the Hudson Valley.)

From the moment that And the People Were With Her (listen here as you read this piece) ended, my “Killer B’s” for the rest of summer 1975 became Beatles, Bernstein, and Bacharach and the west coast became a real contender. John Williams’ pealing orchestral main title to Star Wars in summer 1978 hit me like a hammer, and I was certain — according to my diaries — that I would move to Los Angeles and start work as an orchestrator, perhaps even graduate in time to scoring. The decision was made when mother sent my orchestral Suite for a Lonely City to Helen Coates and in return received a letter — a sort of unexpected musical golden ticket — from Leonard Bernstein which she would open a few feet away from where I was sitting. East it was.

In a few months, Kevin would put Britten’s Billy Budd on the record player, and my future as an opera composer would be set: Bacharach was supplanted by Britten. By the time I graduated high school, the earthy authenticity of Bartok supplanted the Beatles. College in Madison brought Homer Lambrecht’s influence; he introduced me to the Italianate suavity of Berio, and my musical trinity became Berio, Britten, and Bernstein. When I finally landed at Curtis, Lukas Foss got me into Stockhausen — a needed antidote to the polishing and professionalizing I was receiving in my lessons with Ned Rorem — and my world was turned inside out. I dedicated myself to Beethoven, Brahms, and Bach as far as the school and my peers were concerned — heaven knows I had enough to learn about that repertoire! — and holed up at the Free Library with Stockhausen and the eastern bloc modernists in the afternoons. Though I toyed with a career in LA during summer 1988, I ended up moving to Europe instead, returning to New York City for good in 1990.

Being a pianist and devotee of the American Songbook helps one to truly credit the subversive power of Bacharach’s music. Gershwin, Arlen, Kern, Rogers, Porter — the lot of them — were only a few years past. Like Bernstein, Bacharach’s chord choices could be deliciously “classical” (I hear the harmonic choices of Bill Evans), with modulations, shifting meters and phrase lengths. Some of his bridges (my favorite is the wandering and wonderful, take-that-Kern-and-Arlen bridge to A House is Not a Home — listen here) are pure bliss. Like Stephen Sondheim and Bernstein, his tunes could be tricky. But during his Warwick-Alpert years, I sense that something in him led him to craft surprisingly memorable (though, again, deceptively simple yet more than quirky and smart, I’d say inspired) tunes.

I have read that Bacharach will be remembered compositionally as a transitional figure bridging the methods perfected by the 50s Brill Building bunch and rock and roll. Or maybe as the American Michel Legrand. Maybe, but I think that takeaway unfairly diminishes his accomplishment. He was a master of instrumental MOR. (“Middle-of-the-road,” a commercial radio format that includes “easy listening” and can even cover cool genres such as Shibuya-kei and show tunes and not so cool ones like Countrypolitan.) MOR makes musical snobs crazy—particularly when a gifted composer writes it. I love that. It’s subversive, and musical chauvinists just don’t get it.

Bacharach brilliantly subverted commercial music clichés and practices by marrying them (thereby freshening classical tropes and supercharging pop music tropes) to classical chops and compositional procedures not to accompany the dissipation of the valium and martini hazed Greatest Generation, but to underline their societal disillusionment. When James Coburn steps into William Daniels’ den (watch it here) in The President’s Analyst (1967) and Daniels’ character (a gun-toting “liberal”) flicks a switch, filling the room with “total sound,” the music supplied by Lalo Schifrin captured the essence of what I have described elsewhere as that which is “heard in the waiting room of a dentist’s office while awaiting a root canal.” It’s MOR, it’s the seamy underside of the American Dream, and it is glorious.

When Cory, a 35 year old arbitrageur who works at the World Trade Center, arrives and lets rip with a big aria in my operafilm 9/10: Love Before the Fall, he’s characterized by the sort of virile Mike Post television theme (here, or here, or here) from the 70s-90s he’d have grown up with—who knows, maybe watching LA Law as a teenager was what inspired him to become a lawyer! When Bibi, a 21-year-old singer brought up in Los Angeles, remembers her childhood there, she swings into music that could have been lifted wholesale from Nikki (listen here). MOR had served as the background music to their suburban childhoods as much as shag carpeting had comforted their bare feet in the den—one on the east coast, the other on the west. It is my honor to characterize them with the music with which they would have identified. Editing the film, I’ve watched again and again (as only one strapped to a moviola must) as people in the room reacted with everything from delight to contempt to these musical moments, depending on who they think they are or what they think music ought to be.

Bacharach was who he was, and his honor — whether it be in South American Getaway (listen here, where he out swingles the Swingle Singers and puts a pin in Berio’s magnificent Sinfonia), or Pacific Coast Highway (listen here, from 1968) in which he captures the dread-filled determination to be carefree that I still picked up on while driving on it during the 90s to Stinson Beach — was to contextualize his time.

To me, though, the most incorruptible facet of Bacharach’s compositional gift remains the gleaming horizontality of his melodies from which the chords seem to hang like icicles from the eaves of an irregular roofline. Hal David’s lyrics were middlebrow — another thing that made the songs easier to digest than Sondheim’s — but heartfelt and soulful. I was never crazy for the collaborations with Bayer Sager. Elvis Costello’s verse — smart, dark, and probing, was a great foil for the late Bacharach as a songwriter. Bacharach set lyrics as an art song composer would poetry (or as Elton John treats Bernie Taupin’s words, though he is liable to override the lyrics entirely for the sake of a good hook or tune) — permitting the rhythm of the unevenly proportioned lyric lines to generate melodies more like those from an art song than a popular song.

Perhaps, if he had been the sort of man who could have been contained by the eastern seaboard, he would not have toured with Dietrich, courted commercial success, or married Dickinson, or encountered his singer muse Warwick (his Leontyne?) and created I Say a Little Prayer (listen here to it as not just a love confection but as the cri de coeur of a woman whose boyfriend is in Vietnam and you get how his songs can be simultaneously winsome and wise) and a host of other great Motown-influenced gems. Maybe he would have surpassed Alec Wilder’s expectations and created a new American art song repertoire. Maybe he would have been America’s other Samuel Barber. Maybe he did. Maybe he was.