On a shelf in a hallway connecting the chorus and band rooms at Pilgrim Park Junior High School in Brookfield, Wisconsin in spring 1976 dwelt 30 copies of the vocal score of Georges Bizet’s Carmen. Wallace Tomchek, our charismatic, terrifying, wildly gifted, somewhat mad chorus teacher, told me that he intended to stage it one spring, “if ever I have the voices.” An opera? I asked, dazzled. “Possibly the best,” he answered briskly, pulling a score off the shelf and tossing it to me the way that, three years later, literature teacher Diane Doerfler would toss to me a copy of John Cheever’s short stories with a mischievous grin, singing, “Here, read these; he mainly gets it right.” I don’t think that the biology of mustering enough teenage choral students to mount Carmen ever worked out for Wally, but I already intuited that I would be an artist, probably a musician or writer, when he told me to keep the score only a year or two before my brother Kevin gave me the vocal score of Benjamin Britten’s Billy Budd for Christmas, thereby cementing my love affair with opera. I treasure both vocal scores to this day.

That year, Wally required that our parents all purchase for us copies of the beautiful 1970 gold-covered Williamson edition of Rogers and Hammerstein’s The Sound of Music. Wally had (rightly) determined that I was at best supporting actor material and had cast me as Max, a role so integral to the show that they cut his songs when the movie was made. “Piano Reduction by Trude Rittman,” I read on the title page.

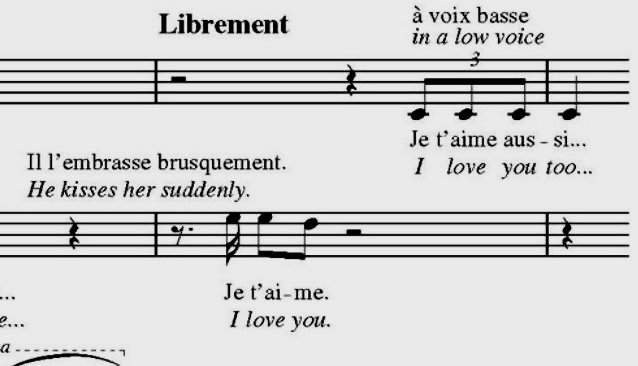

Over time, I came to know (in my heart and in my hands both) and love the smoothly schmoozy feel of playing Frank Loesser vocal scores; the cooly precise, Ravel-like fussiness of Stephen Sondheim’s; the gnarly, saturated chromatics of Richard Strauss’ own piano reductions, with all the heavy lifting in the thumbs and index fingers of both hands; Kurt Weill’s flinty, Hindemith-y piano reductions to his own (European) scores, followed by the more Gershwin-y feel of his (American) scores; Jack Beeson’s scholarly, sensible reductions of his own shows — especially Lizzy Borden; the richly pianistic vocal scores of Marc Blitzstein for his own shows, which feel as though one should be singing them at the piano whilst playing. Things begin to run off the rails with George Gershwin’s own piano reduction of Porgy and Bess, which requires a real pianist — ironically, the hardest music to play is the transitional stuff, which gets all Gaspard de la nuit and requires real chops — to pull off.

Then there are the vocal scores executed not by the composers themselves but by associates: the practical, uninspired, not particularly singer-friendly Erwin Stein reductions of Benjamin Britten’s Peter Grimes and Billy Budd, which I love, but which do not feel good to play; the noble piano reduction by composer John McGinn of John Adams’ Nixon in China — a real achievement — both playable and fun; Noel Coward’s marvelous, splay-fingered vocal scores executed by Elsie April, which always made me want to have a martini at hand; the co-blended vocal score of West Side Story, which is harder to play than it needs to be, and requires the pianistic athleticism of a keyboard jock to get through.

One of the most inspiring things about the lyric theater — by which I mean live theater or film in which people start singing now and then or all the time — is its compulsively collaborative nature. “Composer” can mean the person who wrote the tune, supported by an arranger who either adds chords or serves as an amanuensis to a composer playing by ear, as well as a “dance music arranger” who takes the tune and develops it for a dance sequence. Robert Russell Bennett used to write the overtures to the shows that he orchestrated for Rogers, and for Cole Porter (despite having the chops, having studied orchestration with Vincent D’Indy), for example. Lin-Manuel Miranda’s In the Heights score was powered by Bill Sherman and Alex Lacamoire, who transcribed, arranged and orchestrated the show.

Musical departments gather and congeal based on time constraints and trust: John Williams and Conrad Pope, because of the speed at which musical materials must be generated for film; Leonard Bernstein and Irwin Kostal / Sid Ramin, who were given detailed “short scores” for execution as a 27 piece pit arrangement for West Side Story, freeing up Bernstein’s time so that he could be “in theater” and able to make changes quickly to a rapidly evolving, choreography-heavy show. Or Sondheim and Jonathan Tunick, whose signature sound is as recognizable as was Robert Russell Bennet’s and as important to the success of the shows on which he works. Which brings us back around to the queen of them all: German composer Trude Rittman, whose Sound of Music reduction was just the tip of the iceberg of her involvement in some of the greatest scores in the American Musical Theater.

In fact, the core piano vocal score documents — disciplined, vocally-supportive, easy-to-play while following a conductor’s stick or coaching a singer — of the American MT repertoire are nearly all Trude Rittman’s superb handiwork: Rogers’ great scores (Carousel, South Pacific, Sound of Music, The King and I); Frederick Loewe’s (more ornate, harder to play) Camelot, My Fair Lady, and numerous orchestrations, dance arrangements. What a treat it was to run into her handwriting, and to learn the handwriting styles of all the great orchestrators when I used to hand copy music at Chelsea Music back in the day.

The number of composer executive chefs in the kitchen, the number of sous-chefs, line cooks, and pastry chefs is dizzying and — if one has a taste for playing in a pit or singing on a stage — pretty cool. (The role of composer is entirely different in commercial MT than it is in opera. For example, when Burt Bacharach got the flu and ran behind in delivering songs for Promises, Promises the producer threatened to take on another composer to finish the score.) With all the different crews crafting performance documents in the living theater, there are bound to be myriad variations on what constitutes the best sort of piano reduction for a show. Usually, they come to us like love letters left after the end of a love affair, sitting in a box at a place like Chelsea Music in Manhattan, founded by Don Walker and Mathilde Pinchus, with the name of the show stamped on the side and a big “piano conductor” score bound archivally, leaning hard either to the left or to the right, there to stay until Broadway’s lights (or the office lights) are extinguished for good — or until the creative teams’ heirs transfer the papers to some university’s archives. Otherwise, they sit, awaiting the next revival.

Piano conductor scores consist of a playable piano part and other lines that contain meaningful countermelodies and “fills” that can be assigned to whomever has been hired for the production at hand. They’re sometimes conducted from (Boosey and Hawkes only brought West Side Story’s conductor score out a few years ago, for example), but, usually, the show’s producers have spent just enough on the music to get the cast album in the can and then — man, I’ve seen shows where the “p/c” and the orchestra parts were just left on the stands at the recording session and then … lost, because the show’s impact was so ephemeral and nobody thought it would ever be revived. Anyone who has played a semi-professional community playhouse production of anything has played out of these books (which have gotten pretty slick — particularly when an outfit like Disney owns the copyright), and which often have the name of the player and the city where the “bus and truck” tour last ended. It is such great insider theater lore.

In the musical theater, pianists accept as a matter of honor that their vocal book is itself a malleable, living, evolving thing, and that errors and inconsistencies will crop up during production(s) over the years as changes for various situations are made and unmade. Cuts are made and sewn up, transitions massaged, songs added and dropped.

American opera composers sometimes emerge from the musical theater tradition and are abashed when pulled up short by opera repetiteurs and rehearsal pianists, who typically expect their scores to have been “frozen” and edited. Opera pianists can’t really be blamed for feeling taken advantage of, since they’re being pulled out of their professional comfort zone if they have never ever coached or played a musical. Their default stance is often (though not always) that the composer didn’t have enough common sense or experience to simplify their short score, either by simply supporting the singers the way Rittman’s scores did or leaving them to their own devices and simply presenting the orchestra parts, as Stein’s did. They can hardly be blamed for feeling that, not only do they have to watch the stick, coach the singers, but also piece together an idiomatic part to play.

There’s a lot to sort out here. Full disclosure: It should be obvious by now that I grew up playing shows and operas from all sorts of scores and truly enjoy coming to terms with the different ways that they come to us. I began my opera career fourteen operas ago by crafting my first piano reduction based on the Britten / Stein model with a dash of Rittman. I’ve come at each score with a fresh ear, hoping to capture the psychology of that opera, but — for better and for worse — I have never “coddled” singers by doubling them in the orchestra unnecessarily and I don’t do it in my vocal scores. Because I have always loved browsing the stacks and learning repertoire from the page, I’ve loved crafting the vocal scores myself to my theatrical works.

Decades ago, David Diamond asked me to orchestrate his opera The Noblest Game for Christopher Keene but I said no; Bernard Rands asked me to make a piano reduction of his opera Vincent — ditto, no. Lenny asked me to try to complete Blitzstein’s unfinished Sacco and Vanzetti but there just wasn’t enough of a torso there to flesh out. Back then, I did do the rehearsal piano reductions (still another set of traditions and protocols) of Ned Rorem’s English Horn, Cello, and Flute Concertos for Boosey, but that’s where my career as a latter-day Rittman came to a close.

I myself never, ever use arrangers or orchestrators. Well, I did once and, regretting it, determined to never take that route again. It’s just not my way. I have always composed into full (or, if rushed, a detailed short) score, even when the commissioning agreement calls for a piano reduction first to facilitate workshops. Perhaps, one day I will leave making the piano reduction of one of my operas to someone else, because it is a lot of work, or maybe just to see how it feels. It will probably be done better than I could do it. Maybe when I write an opera without words.

In any event, here are a couple of anecdotes that illustrate the level of mutual forbearance, respect and trust required of opera composers and opera coach / repetiteurs to get the work done.

I remember the conductor of an early revival of my opera Shining Brow who added thirds and (often) unresolved 7ths and 9ths to the piano reduction I had made when coaching. He explained that it helped the singers to find their pitches (I had followed the Britten / Stein model). At the first orchestral read-through, the singers had trouble finding their pitches because they had relied on the extra notes he’d been feeding them.

Another time, during a revival of Amelia, for which the original commissioning contract had stipulated that there would be two pianists for rehearsals, the pianist took me aside and said, “With all due respect, you could have given me a piano reduction instead of a short score to coach from.” The next revival, the pianist, playing out of the newly simplified score, admonished me to put in instrumental cue names so that he could tell the singers “what to listen for” when coaching. (In musical theater scores, such cues are common, and I often put them in, but, for that generation of the vocal score I had removed them.)

Coaching the original cast of Vera of Las Vegas from the keyboard (as I had my previous shows) in Las Vegas, I had delighted in getting every articulation right, every musical style just so, every mannerism notated. Twenty years later, during a European tour, I laughed with the band over beers when they said, “Jesus, you were specific. We know what you want. Trust us. Take them all out.” Too late, the score had been “frozen” years previous.

Some operas, like Orson Rehearsed, are modular, and incorporate lots of un-notateable electronica. Imagine my brilliant conductor’s consternation when the otherwise beautiful vocal score he was using to coach his singers didn’t capture exactly what the electronics were doing. “Once I figured that out, I was fine, but before that, it was touch and go.”

The vocal score of The Antient Concert was, first and foremost, a document of the string quartet arrangement with which the work was first premiered. Jocelyn Dueck, the coach and repetiteur for the original workshop at the Princeton Atelier, was comfortable “dropping” phrases when she needed to so that she could support the singers. The result was that she played an opera score like a musical theater score. She really “got” what I gave her, and I was grateful. When the score was published, I wanted to make sure that the fact that it was not a piano reduction was made clear, so I placed on the title page “Vocal Score by the Composer,” which some clever librarian somewhere catalogued as “Vocal score by [sic] the composer.” Everyone’s so smart.

Recently, I returned to the 2013 piano reduction of A Woman in Morocco to transform it into a Rittman-style score that could be used by traditional opera coaches. In my original development score I found notes given to me by Kathleen Kelly during a developmental workshop of the piece years ago in Texas. An extraordinary pianist, coach, and conductor, she had done such an excellent job preparing the singers before I got to town that, when she asked me about some of the French that I had set in the score, I trusted her enough to ask her to “fix” my French prosody as she saw fit and to teach me afterwards what she had done. I remain grateful.

The musical director (conducting and playing out of a “piano / conductor” score) of a revival of Vera of Las Vegas revealed to me that he had had no problem cueing the drummer in one city, but that the current drummer had sworn that the part was unreadable because several of the instruments were on different lines than he was used to. (He was fired and another person engaged.) “He came to look at his part in the piano / conductor score, laughed, and said, ‘this isn’t an opera, it’s a cabaret. I shouldn’t have to play exactly what’s written!’”

One time, during staging rehearsals of another show, I was asked to step in to accompany a staging rehearsal in which the conductor was consistently behind the beat. I took it as long as I could before (I was younger then) started accompanying the singers and ignoring the stick. The scene, which had been slow and aggravating, sprang into motion like a racehorse. I was thrilled. Finally, I had to admit to myself that I was doing the production a disservice because the conductor had just started following me; as soon as I resumed my place on the sidelines, the old tempi returned.

What have I learned? That every vocal score should be accepted on its own merits because it is the result of the development process by which it was wrought. There is no correct way to execute a vocal score, though a “piano reduction” should be idiomatic and only go to three staves when there’s no other recourse. If a pianist is looking at a “piano conductor” score, then they should know going in that they’ll be required to make a lot of decisions about what to play and what not to. There’s no blame to go around.

Our mission from the piano bench is to prepare the singers, protect them, and support them as best we can. We can’t afford to get lost in the weeds. Our job is stressful and for the most part thankless, but we’re working out of living documents created by people in the thick of creating. Mistakes in vocal scores rarely occur out of ignorance; usually they occur because of lack of experience or time. As a retired Teamster copyist, I’d be the first fella to simply blame the copyist — everyone does. As Lukas Foss used to tell me, “Daron, the ink is wet until you die.” Play on.