Shortly after my memoir Duet with the Past was published more or less to crickets, a cardiologist informed me that I had aortic atresia, a congenital absence of the normal valvular opening from the left ventricle of the heart into the aorta. In my case, the valve wasn’t closing entirely, and was deteriorating, which meant that it would have to be replaced eventually. The news would have made for a great ending to the book, which began with a description of the infant death—due to the same condition—of my namesake. Instead, my narrative ended with a lyrical portrait of bourgeois family life—the story of a fine artist who ended up somewhere in the middle, raising sons, counting blessings and reconnecting with childhood values.

A staccato scene in the doctor’s office followed by the Patient walking out into the parking lot, distractedly pawing at his sternum (as though that would tell him anything) with one hand while processing the news and in the process dropping his keys—an apt metaphor. Curtain. It would have been an effective, full-circle first act break for a tragicomic two act Off-Broadway musical—certainly suitable for an ending to my memoir. As Orson Welles observed in the unproduced screenplay, The Brass Ring, “If you want a happy ending, that depends, of course, on where you stop your story.” And yet.

In My Lost City, Fitzgerald wrote, “I once thought that there were no second acts in American lives, but there was certainly to be a second act to New York's boom days.” Indeed, traditional theater—and episodic television—give one five acts to skid to a halt. I had only begun sketching the treatment for Orson Rehearsed when Duet with the Past was published. I was aware that it would either serve as the beginning of a new act or as the postlude to a life torso.

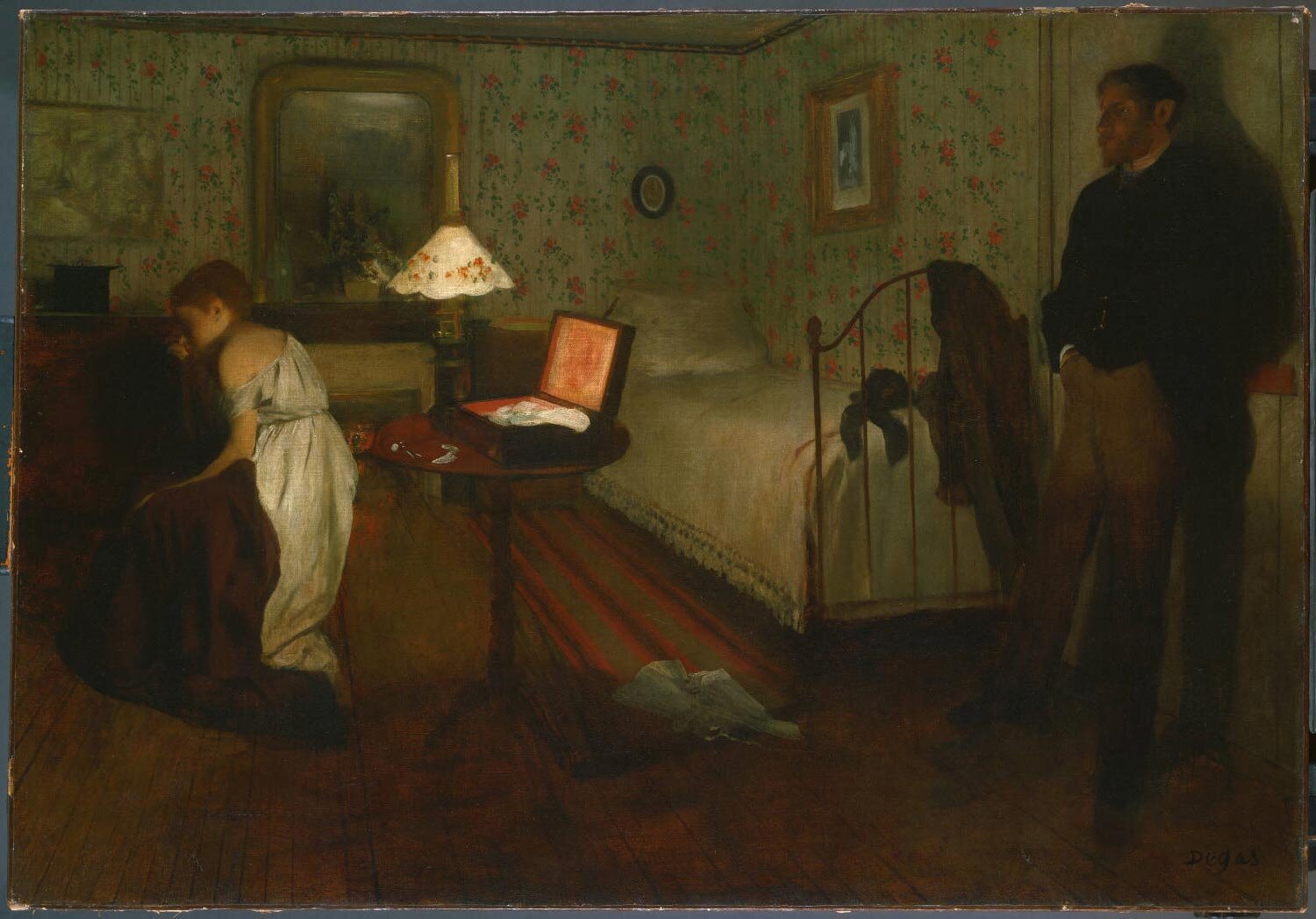

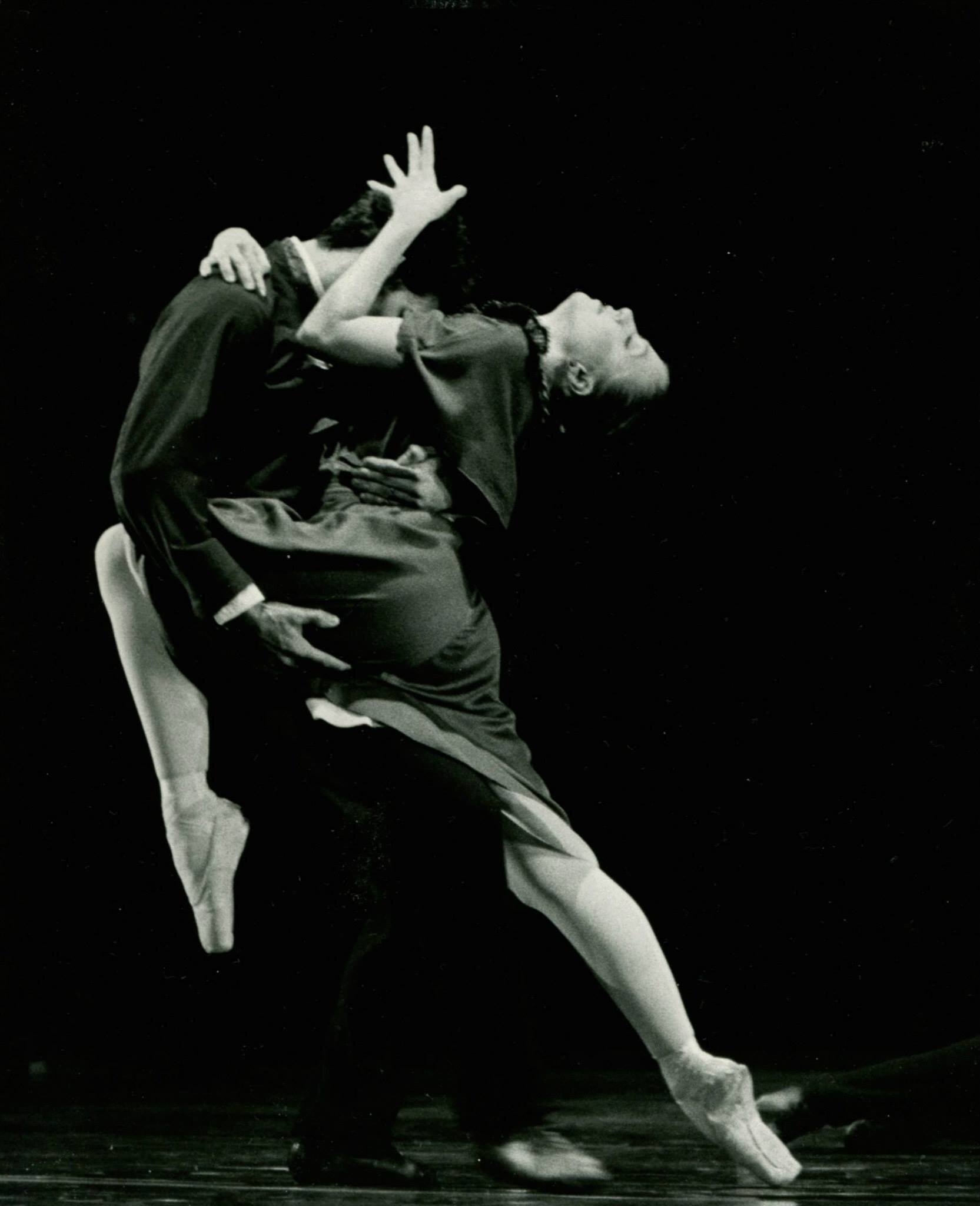

An opera film about a polymath artist dying of a heart attack is obviously an artistic response to the heart disease diagnosis. Orson is postmodern in its disregard for outmoded conceptions of high and low art; it exists after elitism. It isn’t that the music is eclectic, it is that the idea of style is irrelevant. It is post stylistic. As the political tool of the Big Lie roared back into civic life, I expressed the dread I felt as a citizen and father by acknowledging the arbitrariness of traditional narrative, seeking Truth in a corkscrew fashion with the Möbius strip-like dramaturgy of Orson Rehearsed. There’s no happy ending, just death. The curtain falls; the hero simply dies; a solo piano plays a ragtime tune to an empty theater.

Like a terrible vast caesura came the pandemic. The implosion / pulverization of what once constituted the “classical music world” accelerated as big institutions cancelled their seasons and musical careers simply stopped. Faith that it was all but an interval between acts seemed naive. Having finished the sixteen month process of editing the opera film of Orson, I released it into the independent film festival world and was astonished to find that particular scene vibrant and keenly anticipating a return to “normalcy.” Orson began gathering laurels, screenings, and growing legs before the audio recording was released on Naxos. It appeared that institutional support for digital visual content by necessity had increased, and a host of opera presenters, composers, and stage directors took up filmic projects. Companies realized that it costs less to film a new project and to stream it than it does to stage it in a small black box theater.

One obvious thing I have learned by publishing a memoir in middle age is that I don’t get to stop my story where I want to. This morning rain falls in heavy sheets of “white” noise and I sketch the treatment of my next opera film, 9/10. It is—despite the fact that it is set in a restaurant in Little Italy the night before the Twin Towers fell—about second acts, about what happens after the disaster. I am beginning to hear, tuning up in my imagination—very, very far off, and I could be mistaken—the primordial sound of an orchestra that doesn’t sound anything like the orchestra that I grew up loving.

Experiencing 9/11, I remember feeling during the next few years that New Yorkers struggled to begin a new act. For me, it was a new narrative that I didn’t feel as though I wanted to be a part of, so I began to think about moving away. Now, as the pandemic begins to wind down, I sense neither the beginning of the end nor the end of the beginning, but the start of just another act.

So: I choose the beginning of my second act, choose my own post-disaster narrative—one in which the Patient stops pawing at his heart, picks up the keys, and hits the road again with renewed energy because of having committed to listening, defining his weaknesses, and learning.

Click on the arrow below to watch the teaser for 9/10.