Risking Lot’s wife’s lot, poring through a box of old pictures the other day, I came upon a posed portrait of me with my arm thrown around the shoulder of someone with whom I once felt close. I thought of Maya Angelou: “When someone shows you who they are, believe them the first time.” Another picture, a candid of me accompanying a young violist at the Camargo Foundation, an artist colony in France, came to hand. I couldn’t remember her name or the name of the piece we were playing, but I could remember the tune and what key it was in. I remembered the smell of lavender and the Med wafting through the half-opened French doors. The abductive reasoning “duck test” came to mind: “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.” Chuckling, I thought then about the “Duke” (Ellington) test: “If it sounds good, it IS good.”

I began thinking about the role that paradigmatic imagery versus syntagmatic has played in shaping the way that I think as a composer and dramaturge.

Just as every image one sees brings another to mind, everything one hears inevitably reminds one of something we’ve heard before. Composers are mockingbirds. What of originality? Musical allusions, outright quotations, sampled recontextualizations, false recollections, received opinions, sentimental reverence for the canon, social engineering, and the understandable human desire to be loved—maybe what saves composers in the end is the fact that music itself is an abstract artform.

Just as every piece of music brings another to mind, everything one sees inevitably reminds one of something we’ve seen before. Portraits are generally paradigmatic, static in nature; they are staged, inherently theatrical; they are artificial portrayals of the “truth” in the moment, or the subject—think mashed potatoes standing in for ice cream. Candid photos are usually syntagmatic, narrative, “frozen moments,” or augenblicken—think movie stills; the term “candid photo” itself imbues, or at least encourages the viewer to infer that, because it was captured in medias res, it is somehow honestly derived.

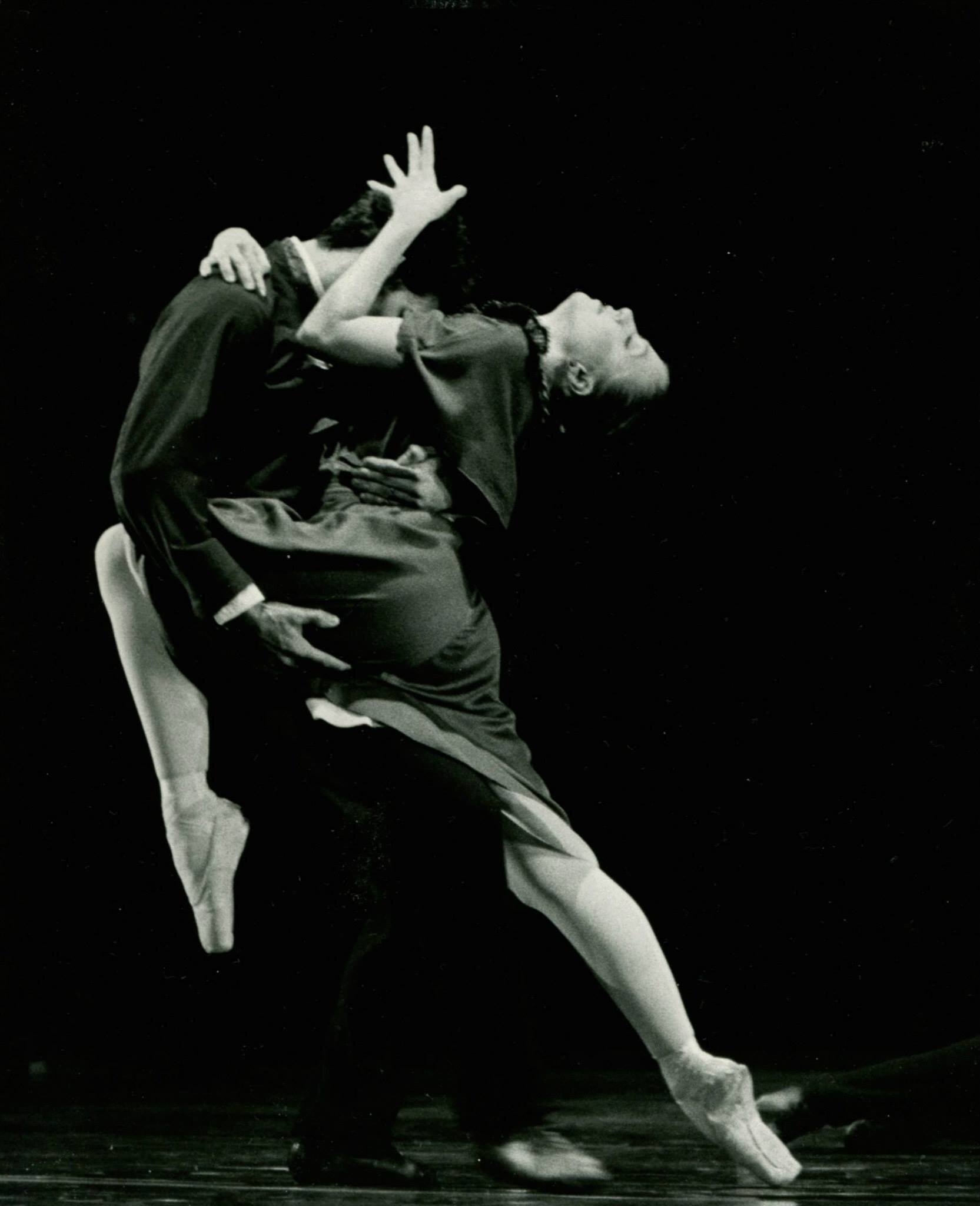

Closing pas de deux from my ballet "Interior," based on the Zola novel, "Therese Racquin," choreography by Diane Coburn Bruning commissioned by the Juilliard Dance Division, Muriel Topaz, director, for their 1989 spring gala, with Bruno Ferandez conducting the orchestra, 17 April 1989.

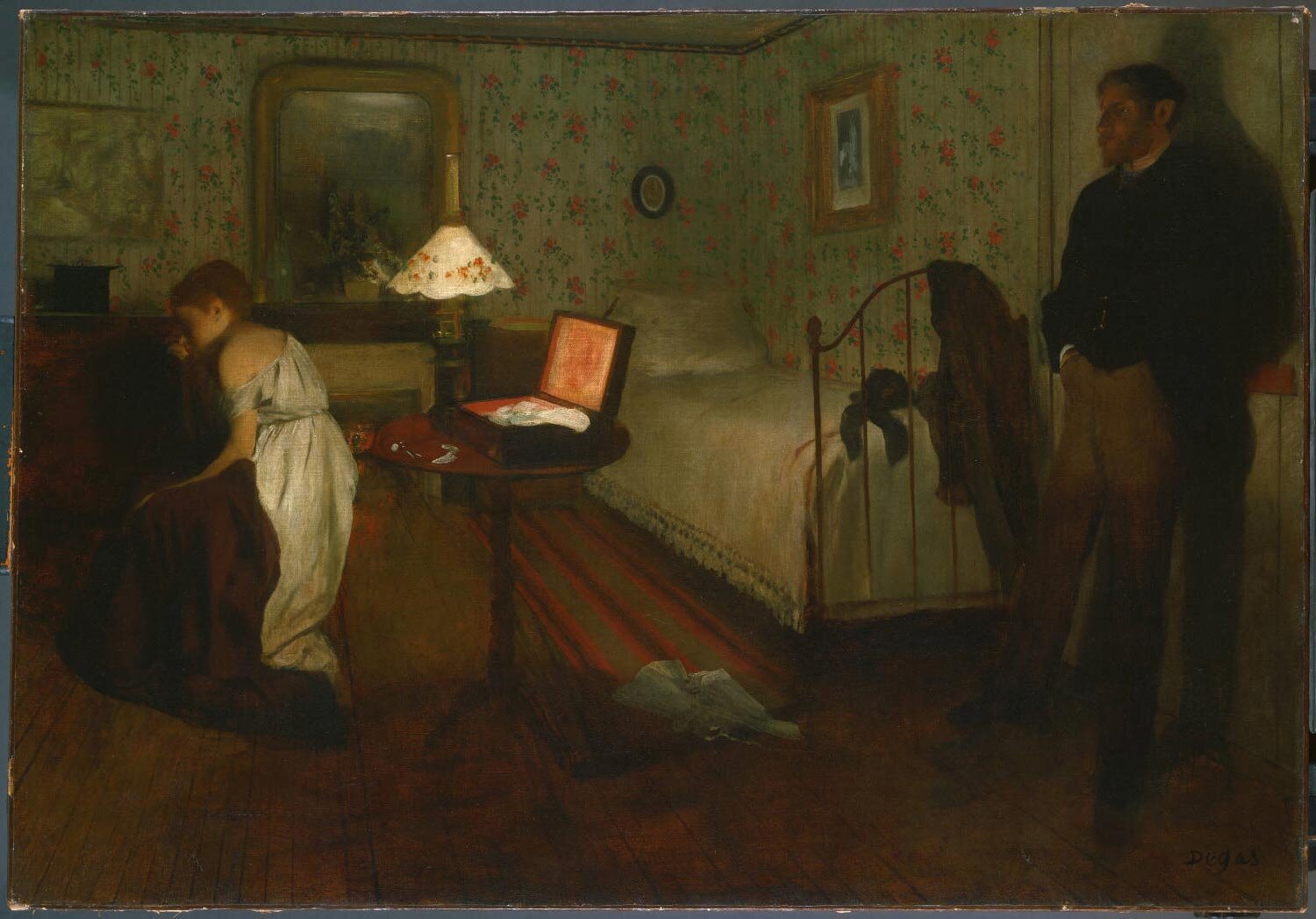

I first got to know Edgar Degas’ great painting Interior, or Le Viol in 1972 as a child from a reproduction in a coffee table book belonging to my mother. Precisely ten years later, to my astonishment, I first saw the original hanging over the couch in Henry McIllhenny’s living room in Philadelphia, having been taken there by my teacher Ned Rorem for tea. It now hangs in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. I’ve read somewhere that Degas himself refered to it as “mon tableau de genre,”—as a “genre” painting outside of his usual fach. It combines decorative elements, such as the wallpaper; theatrical ones, like the consciously syntagmatic, theatrical placement of the characters and narrative ambiguity—the title encourages us to respond to the dramatic tension created by the competing visual rhetorical languages: the elements in the painting clash, paintings within the painting distract and compel. Degas places directly before the viewer a mirror into which, should we by chance look deeply enough and, if only Degas had not shielded us from ourselves in it by making the image indistinct, we would see ourselves—complicit voyeurs taking in a sordid and painfully human scene.

Degas is said to have drawn inspiration from Emile Zola’s great novel Therese Racquin, in whose characters this transgressive power dynamic is forcefully explored. Diane Doerfler, my high school literature teacher, tossed the book my way in 1979. Eyebrows arched mischievously, she promised that I’d “find an opera in it.” During fall 1985 I dipped into sketches I was making for one to craft the second movement (“Interior—after Degas”) of my Piano Trio No. 2 for the Lehner Trio, who debuted it at Alice Tully Hall at Lincoln Center during spring 1987. By then, choreographer Diane Coburn Bruning and I were casting about for a subject for a new ballet, which we called Interior, commissioned by Muriel Topaz for the 1989 Juilliard Dance Division’s spring gala. I suggested the Zola, and we were off. Diane’s choreography juxtaposed and interwove a traditional narrative (we tracked the lovers’ story) with abstract (decorative?) moves for the ensemble.

When Seattle Opera commissioned me to craft the large-scale opera Amelia in 2005, our creative team intertwined mythology, fantasies, simultaneous timelines, and rhetorical juxtaposition to create context to convey the story of Amelia, a mother-to-be at full term coming to terms with the childhood loss of her naval aviator father had been lost at sea during the Vietnam conflict. In one example of combining the paradigmatic and syntagmatic, a climactic quintet during the second act featured Amelia’s aunt praying in real time while seated next to the unconscious Amelia in one hospital room, Amelia Earhart emerging from her downed aircraft in Amelia’s imagination, a father and son who is succumbing to injuries sustained in a fall from a great height (who may or may not be Icarus and his father Dædalus), and Amelia’s dead father, in dress whites, urging her back to life.

A screen grab from Orson Rehearsed.

Orson Rehearsed, my 2021 opera film, explored the interior of Orson Welles’ mind as he comes to terms not with the bardo of giving birth to a baby, but with the bardo between life and what comes after. Like the viewers of Degas’ painting, the audience at once witnesses both a portrait and a staged tableau. In Orson, not one but three “realistic” avatars strive to braid themselves into a coherent understanding of what is happening to them, accompanied by movies that reveal the (entirely subjective) images inside their minds. Together, they perform “live” with music both acoustic and canned, both “real” and “synthesized.” The “live” performances they give are then recontextualized on black and white film inside an otherwise full-color film that treats their live performance as but one of multiple elements—the others being single-color screened stills from elsewhere in the narrative, and a complete storyline for a mute character (the “Departing Boy / Youngest Orson”) who exists only as fragments of public domain stock footage from the 30s and newly-shot footage with a child actor (my son, at the age of nine). At the climactic moment in the opera film, (“Myocardial Infarction,” or the instant of his death), Welles’ consciousness extends from the instant of his demise into the past and the future. One of the Orsons sings Emma Lazarus’ 1903 sonnet “The New Colossus” as a reminder that Rhodes fell, that the library at Alexandria was sacked, that, as Matthew 24:6-8 reminds us, “all … things must come to pass, but the end is not yet.”—only, in Welles’ case, it is. Or maybe not. A second Orson sings the repugnant words of the reptilian lawyer Roy Cohn; the third smugly spews the tweets of a “reality television show politician” from 2019.

Observe (in addition to the fascinating lagniappe) in this still from the faux newsreel shown at the beginning of Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” how Welles characteristically delineates foreground, middle ground, and background action, overlaying overall the chiaroscuro of a shadow.

I drew some more pictures from the box. A snapshot of my high school sweetheart came to hand. “Is all that we see or seem,” asked Poe in 1849, “but a dream within a dream?” On the piano rack behind us sat the manuscript of a setting of Poe’s poem that I had just made for her. I found the sheet music, published a few years later by EC Schirmer, and had empirical proof of the “truth” of the fact that it was composed on Christmas Day, 1981. Why? Because there it was, in a published piece. It must be true, right? But I don’t remember being there. Remember Turgenev, in 1862, in Fathers and Sons, when he rolled out this heartbreaker: “The drawing shows me at a glance what might be spread over ten pages in a book.” Indeed, I have forgotten so much now; and such strange new memories have begun to surface after the publication of my memoir. In truth, I had forgotten that the song was written for her in the first place. The picture brought it all back in a flash.

I closed the box, taped it shut, and wrote “OLD PICTURES” on it with a sharpie before stowing it away, probably not to be opened again for another twenty years. For some reason, I thought for an instant of a recent, rather nasty review in which a freelance writer/composer had described Orson Rehearsed as “a hectic 60 minutes with a tendency to cliché (‘we are all alone’) and cod-metaphysics (‘eye equals I’)” and was reminded that one is never clever enough to play that game. The quotations, of course, like most of them in the piece, were Welles’ own public domain utterances. As for the word cliché, slipped in like a shiv, the writer is saying that my work betrays a lack of original thought. The Internet being what it is, I went to the computer and listened to some of the critic’s music, took the work’s measure, and smiled inwardly, for—to paraphrase Plato—beauty truly is in the eyes of the beholder.