Daron Hagen is an American composer, filmmaker, director, and author. He made his debut as a director mounting his own works at the Kentucky Opera in Louisville; he has also directed his works at the Skylight Music Theater in Milwaukee, the Chicago Opera Theater, and others. He is currently directing a film version of his opera Shining Brow for Ohio Public Television.

It was truly our pleasure to interview Daron Hagen for Chicago Movie Magazine.

1. What draws you to filmmaking, cinematic language and composing music for film?

I started watching films critically in my late teens at the Oriental Landmark Theater in Milwaukee at exactly the same time I started digging into music composition and its attendant commentary. The Oriental was a glorious, ramshackle calendar house that showed all sorts of films—from Fellini to Scorsese, Welles to Wenders, Chaplin to Kieślowski, Ford to Ford Coppola, Kurosawa to Lucas. Around the same time, I began reading film criticism and theory—beginning with Truffaut’s incendiary screeds. I am drawn to film because, setting aside the crucial component of live performance, it does everything that opera does and in much the same way.

Operatic scores and filmic documents convey narrative and control dramaturgy through manipulating time and fundamentally altering our perception of its passing. Film’s visual and sonic rhetoric creates the reality in which the narrative unfolds, exactly as opera sets forth an assemblage of gestures, timbers, moods, and sticks to them. As a composer cutting film, I feel the way that I do when I am composing and orchestrating music: one’s choices are guided always by the desire to clarify and illuminate the dramatic and emotional nuclear reactor firing the scene; rhythm is paramount, transitions are where the emotions shift.

Opera composers have traditionally been treated, like auteur filmmakers, as the genre’s visionaries. The opera house is a vast mechanism filled with profoundly gifted technicians, directors, and craftspersons, all of whom are happy to spray Febreze on mediocre operatic product if they must, just as the artisans in a film production company do.

In the US at least the opera world seems to have shifted away from the traditional idea of the composer leading a team of collaborators gathering together to illuminate and enhance the composer’s intent. In addition to the much-needed heavy-lifting being done by opera producers in terms of fostering a collaborative environment that reflects current ideas of racial and gender equity, there has been a systematic reevaluation of the composer’s role in the collaborative process: just twenty years ago, treating opera composers like commercial music theater composers still seemed to be at least a short-term path towards dismantling the 19th century “great man” model. For many of my colleagues, the opera composer’s role now is that of a member of a creative team led by the director or the producer.

As a lifelong learner and personal reinventor, I decided to move laterally into directing my own operas about ten years ago because I wanted to explore the similarities between stage and cinematic languages and directing. Although absolutely delighted as a composer to provide music for a film perfectly pitched to serve the director’s and music editor’s vision if required, I realized that I could only explore the territory between the two disciplines if I not only created the score, but also wrote, directed, and edited the film to the score, adjusting each to the other to form a more perfect dialogue between them. In order to maintain the frisson of live opera’s visceral appeal (and palpable risk), I needed to create a production process that allowed for there to be a live production as part of the progression towards the screen.

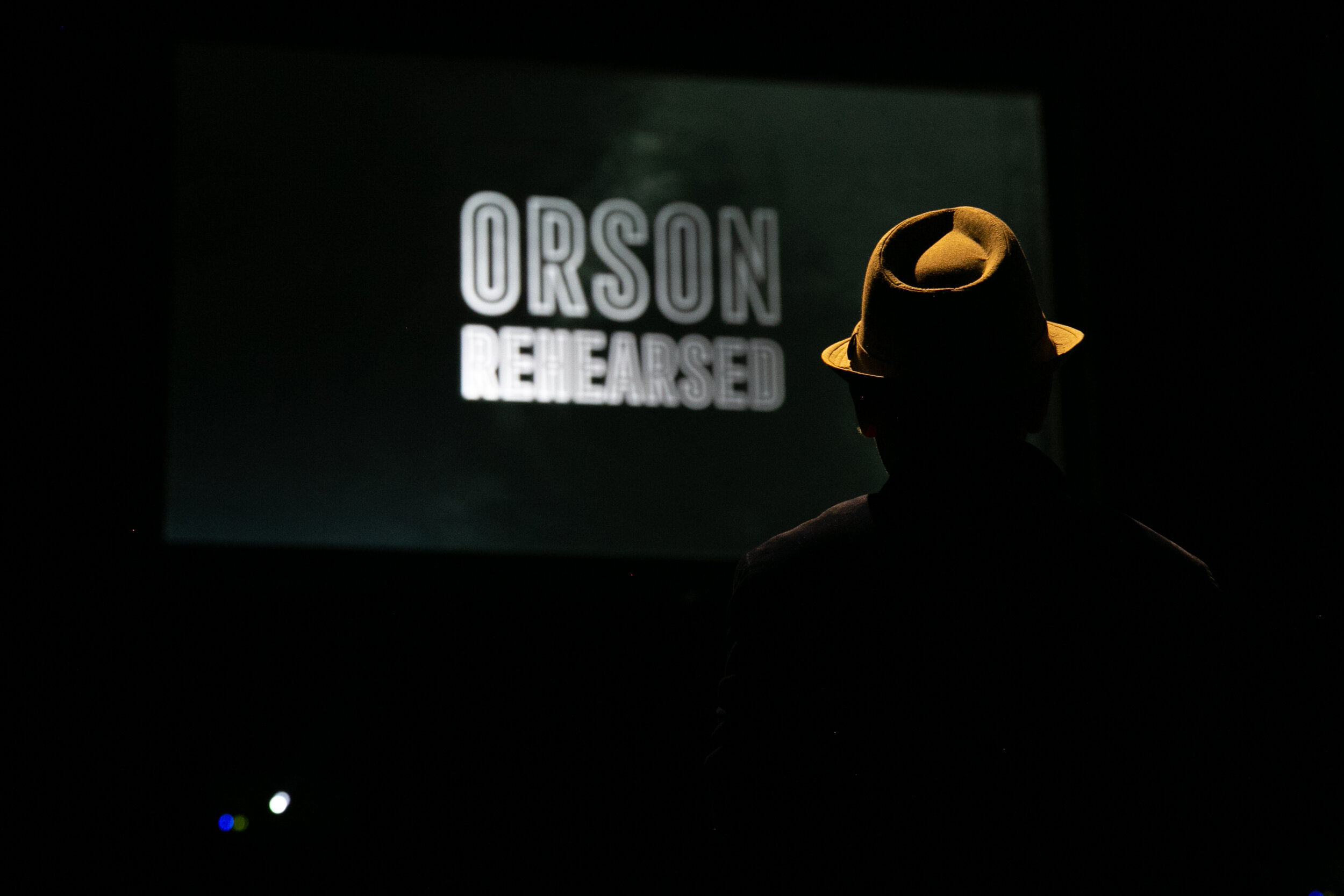

I formed The New Mercury Collective, a loose association of actors, singers, writers, and designers with whom I had made crossover projects over the previous thirty years utilizing both Music Theater, Opera, and Filmic staging techniques. This would be my sandbox, and the place where I would create Orson Rehearsed, which I knew from the very start would end up as a film and an open-ended music-theater piece that would constantly change shape depending on the circumstances.

2. Do you believe in film schools or does making a film teach you more than film school?

I did not go to film school, so I don’t know. Since I learned how to write operas by accompanying them, singing in them, writing them, conducting them, and directing them, it seemed sensible to me to learn filmmaking the same way—by taking on the genre’s constituent tasks and learning by doing. I did go to Juilliard and to Curtis to study music, so I have some pretty strong ideas about what I learned at those places, and what I didn’t. For example, I am astonished that student composers are not simply required to attend the rehearsals of their local orchestras. Critical listening (to actual performers in situ performing one’s own and others’ music) teaches more about composing than does any class because you can hear what works and what doesn’t—and when it doesn’t what the performers have to do to make it work. Perhaps I am projecting, but I imagine that nascent filmmakers encounter pretty much the same terrain in film school.

3. What makes cinema stand out more than the arts for you?

I could never relinquish live theater—making it with others and watching it has given me the most fulfilling personal and aesthetic experiences in my life. During my lifetime, technology has made it easier, faster, and cheaper to write film operas than staged operas.

4. Did you choose a certain directing style for making this film based on the script?

I have cool adoration for the subversiveness of Truffaut’s Doinel films and an appetite for the ethical earnestness of Rod Serling’s morality screenplays. My mother was a visual artist and took pains to explain Welles’ techniques to me when together we watched Kane when I was a kid. But my roots are in opera, so I warm to Fellini’s aesthetic of intensity: I like to create environments that are so fake that they create their own reality. Film is great at this sort of subterfuge—even better than live theater, but not better than a live magic show.

It was pretty early in my career as a composer of large-scale works for orchestras and opera companies when I really came to terms with the concept of strictly terracing simultaneously presented ideas. Composer Nicolai Rimsky Korsakov in his Principles of Orchestration lays out elegantly the idea that complex compositions should strictly hierarchize foreground, middle-ground, and background events for the listener through orchestration. Arnold Schoenberg’s string quartets are masterly in their painterly use of relief, chiaroscuro, and “deep action.” The violas in Richard Strauss’ Der Rosenkavalier tell us clearly what the Marschallin is really feeling: either we hear them or we intuit them. Either way, we win. These precepts are no different from Welles’ framing of the father in the foreground, mother and banker in the middle ground, and Charlie and his sled in the background.

For Orson Rehearsed I shot about thirty hours of full-color video to create three 60-minute films that portrayed the internal thoughts of three onstage singers who portrayed Orson Welles inside his own mind. Into this I mixed about ten minutes of licensed and public domain archival footage. The films constituted the background images (all tied to musical ideas in the score, of course). The foreground images in the film are all in black and white and consist of the reality played by the avatars themselves as they sing. Between the two (like the violas in Strauss) flows a layer of ghostlike, semi-opaque single-color images drawn from the upper and lower layers of rhetoric that superimpose themselves like fleeting thoughts and then disperse. The Process was: shoot the background films, stage the foreground action, then, formulate the middle layer while editing together the top and bottom layers.

Omar Mulero

Robert Orth

Robert Frankenberry

5. How did you choose the cast and the crew of your film?

I had already created my Collective and intended to draw from them the team needed for this project. But I needed not one but three Orson Welles avatars: a youthful, middle-aged, and dying Orson. As a faculty member of the Chicago College of Performing Arts, I was able to cast the young Orson with Omar Mulero, a gifted tenor and graduate student there, then just beginning his career.

For the middle-aged Orson, I knew beforehand that I would write for Robert Frankenberry, a prodigious musical and theatrical polymath (conductor, tenor, stage director, composer, pianist) who I had cast as Louis Sullivan in the Buffalo Philharmonic’s recording of my Frank Lloyd Wright opera Shining Brow and who had gone on to conduct the orchestra in a revival of the opera in a site-specific staging at Wright’s Fallingwater a few years later.

I’d known for nearly a decade that I was going to write the role of the dying Welles for the legendary baritone Robert Orth. Bob was a fiercely capable, emotionally brave intellect and performer who could suavely straddle the American Music Theater and Opera traditions. The “go to” baritone for an entire generation of well-known American opera composers, Bob and I had first crossed paths when the terrific director Ken Cazan had cast him in a revival of Shining Brow with the Chicago Opera Theater in the 90s. As it happened, Bob was receiving chemotherapy during the staging and filming of Orson Rehearsed. His performance was nothing less than heroic, and he passed away a few months after production.

Having these three men go through the discovery and staging process together, and serving as their composer and director, was really, really moving—the most fulfilling experience of my career in the theater. The give-and-take between them—Bob’s wisdom and experience, Frankenberry’s brave questing, Omar’s open, honesty—soaking it all up, glowing and growing in the process—amazing. It’s why I committed to the theater as a teenager and why I’ve remained so.

While staging my opera A Woman in Morocco for Kentucky Opera I had the good fortune to collaborate with lighting designer Victoria Bain, with whom I explored a lot of the Jean Rosenthal-inspired effects I wanted for that production. For Orson, she graciously jumped in to the Kieślowski-esque Red-White-Blue aesthetic I had in mind for Orson Rehearsed (I first fell in love with this when composing the opera Bandana back in the late 90s—the vocal score is chock-o-block with lighting cues that most theatrical lighting designers ignore) and she nimbly avoided most of the pitfalls inherent in lighting a stage show that was going to be folded into a movie but still had to look good in the theater. There was an able young team in Chicago called Atlas Arts Media that were then just getting on their feet that was able to adroitly handle both the camera emplacements I needed for coverage and the live mix of sound for the soundtrack and CD-release of the score.

Conductor Roger Zahab and Hagen during production at the Studebaker Theater in Chicago. (Elliott Mandel photo)

6. How did you fund your film and what were some of the challenges of making this film?

The Chicago College of the Performing Arts served as a production partner in exchange for their students shadowing me as composer, director, and independent artist, as well as being cast in productions that combined both seasoned professionals and emerging artists. They shared costs with my New Mercury Collective. It is basically a sandbox, or, as Welles would say, a train set, in which I build my little sandcastles and operatic locomotives. I have more creative control than I do when I work with an opera company, but less money. On the other hand, technology has made it cheaper to make films; so long as you have the skills to wear a bunch of different hats, you can arrive at the end with something that looks and sounds pretty good.

The major challenge of production was the real-time coordination of my elaborately-crafted electro-acoustic tracks, the live onstage ensemble of eleven instrumentalists (the Chicago-based Fifth House Ensemble), the three live singers in performance with the three sixty-minute films, and the three onstage sixty-minute films on a low budget. The credit goes to composer / violinist / conductor Roger Zahab, who held it all together from the podium. The team at Chicago’s Atlas Arts Media mixed the show in real time while also giving me basic camera coverage so that I could embark upon the next leg of production with hard drives full of soundtrack ready to be mixed, and shots ready to be edited together.

7. Do you consider yourself an indie filmmaker and what would most be the most difficult thing about being an independent artist?

I have been an independent artist all my professional life, so moving sideways into the creation of indie film has been a deeply pleasurable learning experience; one that feels like donning a familiar and much-beloved old sweater. Though I’ve served on the faculties of Bard College, Princeton, and Curtis, among others, they were always adjunct positions—however long-term, that helped to pay the bills so that I could make more art. I’ve been lucky, but I’ve always been a very hard worker, and I’ve been supported by a lot of really generous people, been given a lot of opportunities to learn my craft and to grow up in my chosen fields. The indie film world of makers, presenters, and festivals is on first take a more mutually supportive scene than the concert music world.

8. What is the distribution plan for your film?

Since I am learning as I go along, I am simply entering the film into festivals and finding out who actually watches it carefully enough to find value in it. If it lands with enough people it will get legs, just as operas and concert pieces do. I realize that “legs” in this case means a distributor. If it doesn’t, then, well, nobody got hurt: in the process of making it I lived my best life, and I made a piece of art about which I care passionately.

9. What is your cinematic goal in life and what would you like to achieve as a filmmaker?

I’ve got several projects already in pre-production that carry forward the methods (combining music and image, film and live theater) I’ve been steadily digging into over the past 20 years. I’m slated to direct a filmed version of my opera Shining Brow at the Frank Lloyd Wright-designed Westcott House with the Springfield Symphony and Think TV (the Dayton PBS affiliate) next year. I’m also filming my next film/opera 9/10, set in an Italian restaurant in Little Italy the night before the Twin Towers fell, in Chicago, in spring 2022 in another CCPA-New Mercury Collective co-production. I’m taking things as they come and scaling things in order to match vision and budget sensibly. My ultimate goal is to gain complete fluency in the idiom and to work at the highest levels with collaborators from whom I can learn the most.

10. What kind of impact would your film have in the world and who is your audience?

Chris Lyons Illustration

I am thinking of this film the way that a poet thinks of a poem and a serious opera composer builds an opera: it is dense, highly allusive in its methods, and it benefits from repeated viewings; Orson Rehearsed delves with subversive lightness into some pretty dark and scary places. I am not expecting it to be “popular” in any sense of the word; it is an “art film,” that will land with people who bring an open mind and heart to it.

11. Please tell us more about the Chicago College of Performing Arts and your involvement with the institution.

Rudy Marcozzi, rock-solid Dean of the Chicago College of Performing Arts, and Linda Berna, Associate Dean and Director of the Music Conservatory, understand that my values as a citizen and as an artist are in synch with Roosevelt University’s as an institution. The school maintains Opera and Music Theater programs side-by-side. I am grateful to have been encouraged by the faculties of both divisions to work freely with their professionally bound singers on my compositions, which consciously combine the technical and aesthetic methods of both disciplines in our uniquely American way. With their guidance, I cast CCPA’s young artists in projects that also feature mid-career professionals that I draw from my Collective, from whom (as Omar did in Orson) they learn through collaborating and observing during production. In addition, I invite the composition students—who study under the strong, mindful leadership of composer / visual artist Dr. Kyong Mee Choi—to serve as members of my production teams, to assist me as director, and so forth, to be immersed as composers in the production of opera and film in a way that they cannot elsewhere. I can’t tell you how supportive the faculty at CCPA has been of this atelier / sandbox / train set nestled within the various conservatories that make up the school.

Official Trailer.

This interview originally appeared in the October 2020 issue of Chicago Movie Magazine and may be accessed there online here.